No-Input Mixing is a strange and somewhat counter-intuitive process of generating sound from a mixing board without external sound sources. In its essence, it involves routing mixer outputs back into inputs, creating feedback and oscillations largely driven by the self-noise of the device. In this article, I’ll take a look at the historical precursors, provide a “recipe” for a no-mixer set-up, and some examples.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

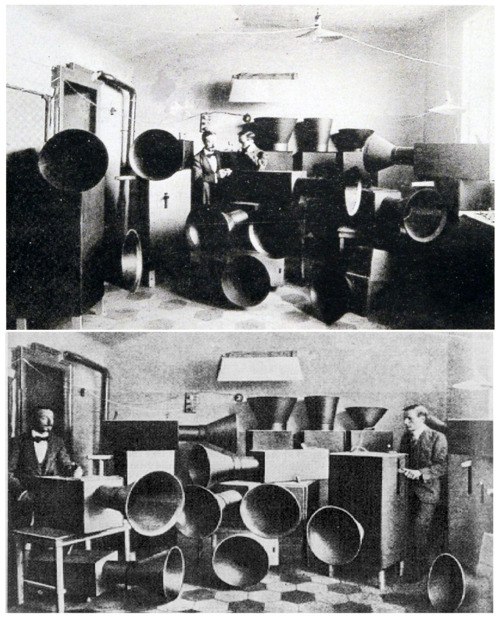

Many people might be surprised that the practice of noise-based music can be traced back over 100 years. Consider the work of Italian futurist, Luigi Russolo and his iconic collection of experimental musical instruments called, Intonarumori.

In Russolo’s manifesto, The Art of Noises, he comments on how the urban landscape and the industrial revolution had changed the expectations of the human listening experience. Rather than discarding or avoiding these sounds, he considered them as an opportunity to explore new sonic colors and to “…substitute for the limited variety of timbres that the orchestra possesses today the infinite variety of timbres in noises, reproduced with appropriate mechanisms” (Cox 13).

The term appropriate mechanisms here is relevant because in Russell’s day, electronic instruments and magnetic tape (1928) were not yet invented or in their nascency. For instance, the Theremin was patented in the 1920’s by Russian physicist Lev Sergeyevich Termen (Miller) and magnetic tape for recording sound was invented 1928 by German engineer, Fritz Pleumer (Fritz). So Russolo built his own devices using a mechanical approach.

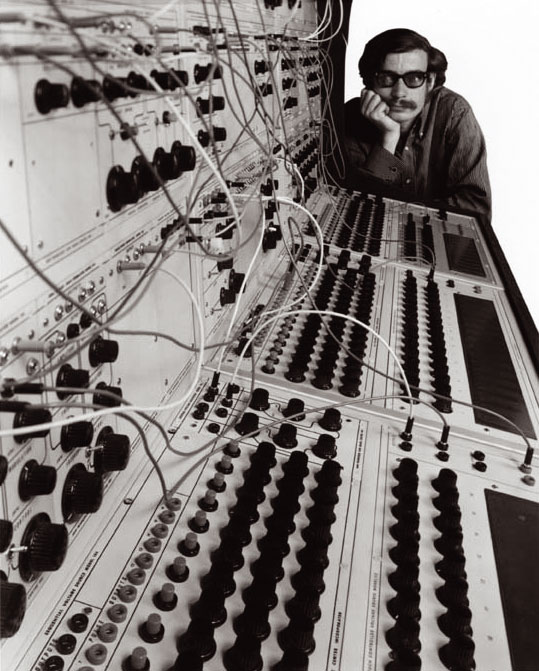

How an instrument is played or how sound is produced can have lasting significance. Jumping ahead in the chronology a bit, most synthesists today are aware of the West Coast / East Coast schism of sorts that resulted from the divergent paths of Robert Moog (East) and Don Buchla (West). Both developed new electronic instruments and although there were differences under the hood, the main distinction was the user interface. Where Buchla believed new sounds demanded new interface controls, Moog adhered to the existing paradigm of a traditional keyboard. The latter made accessibility much more attractive to keyboard players who already possessed a playable skill-set, which could explain the prevalence and commercial success of Moog synthesizers in the years to come.

Robert Moog and Herb Deutsch (moogmusic.Com)

As the proliferation of new technology accelerated in the 20th Century, artists were among the first to subvert prescribed uses.

John Cage’s, Williams Mix (1951-1953) (Williams) undermined the linearity of tape recordings through the meticulous and painstaking splicing of recordings based on I Ching manipulations. With the assistance of Earle Brown, Morton Feldman, David Tudor, and Bebe and Louis Barron it would become the first octophonic piece of music. I had the honor of meeting Earle Brown in the late 90’s at a rehearsal of his landmark piece, Available Forms, to be performed by the SEM ensemble with Petr Kotik conducting. I asked him about Williams Mix and his response was, “I’ll never do that again”–referring to the labor-intensive process of splicing over 3000 tape fragments.

Pierre Schaffer is primarily known for his concept of musique concrète, developed in the 1940s and based on using recorded material as content. Recordings of instruments, voices, electronics, ambience, were all fair game. This approach established the idea of the sound object or l’objet sonore, which was distinct from the abstract idea of musical notation (Nyman 48).

Sound started to become more prevalent in visual and other performance arts around this time as well. The late 50s, Happening and Fluxus artists, Allan Kaprow and George Brecht participated in John Cage’s experimental composition classes at the New School for Social Research in NYC. Kaprow commented to Brecht that he “…wanted to better integrate sound into his artwork and to become…a noisician” (Kahn 275).

Most every composer from the middle of the century onwards began to explore electronics and new mediums including Pierre Henry, Steve Reich, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Iannis Xenakis to name just a few.

Around 1966, Reed Ghazala accidentally discovered a technique he named, Circuit Bending–the process of rewiring and short-circuit consumer electronics to produce all sorts of glitchy and unpredictable sounds. He observed, “Because no one can predict the outcome of circuit-bending, you’re taking a journey into unknown territory here. All you can do is approach with the right attitude and tools to get the best shot at good results (Gottschalk 62). To read more about circuit bending check out Jeff Boynton’s article, “The Black Art of Circuit Bending” (Boynton).

In the 60-70s more mainstream artists began to experiment with tape manipulations including The Beatles (Tomorrow Never Knows), Frank Zappa (We’re Only in it for the Money and Lumpy Gravy), The Residents (Beyond the Valley of a Day in the Life – using samples from the Beatles) to name a few. These developments were precursors to the use of sampling in Hip-hop, DJing, turntablism, and scratching.

Compact Discs entered the market early 1980s promising to be a pristine noise-free medium with an expanded dynamic range. A decade later the German trio, Oval would release Systemisch, an album that used deliberately damaged CDs to create a glitch aesthetic (Cox 393)

In the 90s, the noise movement erupted in Japan–referred to by many as Japanoise. (Japanoise). Artists like Merzbow, Hijokaidan, and Incapacitants embraced noise and free improvisation in a variety of ways.

Merzbow (Cox 59) is the recording name of artist, Masami Akita. Talking about his set-up in the late 80s, “Equipment included an audio mixer, contact mic, delay, distortion, ring modulator and bowed metal instruments. Basically, my main sound was created by mixer feedback”.

Akita has said that “…if music was sex, Merzbow would be pornography” and “…pornography is the unconsciousness of sex. So, noise is the unconsciousness of music…for me Noise is the most erotic form of sound” (Cox 60).

“The word, “noise” has been used in Western Europe since Luigi Russolo’s, The Art of Noises. However, Industrial music used “noise” as a kind of technique. Western noise is often too conceptual or academic. Japanese Noise relishes the ecstasy of sound itself” (Cox 60).

TOSHIMARU NAKAMURA’S NO-INPUT MIXING

Perhaps the artist most identified with the practice of No-Input Mixing is Toshimaru Nakamura, (Toshimaru) another experimental musician from Japan. He was part of the Onkyokei (meaning–sound, noise, echo) movement in the late 90’s, although he and other artists involved objected to the term because it seemed to homogenize the individual variations in approach (Onkyokei).

According to Nakamura, “…the unpredictability of the instrument requires an attitude of obedience and resignation to the system and the sounds it produces, bringing a high level of indeterminacy and surprise to the music” (Toshimaru).

In an interview with Nakamura from the early 2000s, he talks about his transition from playing guitar to no-input mixing.

When I stopped playing the guitar it’s like I noticed, I found out I can’t play the guitar anymore because I felt the guitar is not my instrument anymore. Because you need something to express, you need some movement to play the guitar. I slowly, gradually found out this was not something I wanted to do. And then one day I played the guitar with the mixing board first, with some effects, with a couple of effects, and I would touch a string on the guitar, and touch some knobs and change parameters of effects units. In the course of this trial I found myself touching the guitar less and less, and doing other things with the mixing board effects more and more. I thought OK, maybe just unplug the guitar from the mixing board and try it without guitar. It’s more focused. When I am on stage with the guitar I just stiffen, my body is really stiff and it refuses to play the guitar, so I just got rid of the guitar and I felt really comfortable. I don’t know why I feel so comfortable, but I just naturally started to create music again.

I think I find an equal relationship with no-input mixing board, which I didn’t see with the guitar. When I played the guitar, “I” had to play the guitar. But with the mixing board, the machine would play me and the music would play the other two, and I would do something or maybe nothing. I would think some people would play the guitar and create their music with this kind of attitude, but for me, no-input mixing board gives me this equal relationship between the music, including the space, the instrument, and me (Toshimaru Nakamura Interview)

NO-INPUT MIXING SET-UP

As a composer and experimentalist for the past three decades, I’ve explored all sorts of methods for producing sound including extended techniques for traditional instruments, musique concrete, circuit bending, acousmatic music, algorithmic and computer-generated music, many forms of digital and analog synthesis, and field recording. However, my experience with no-input mixing is minimal. So in preparation for this article, I dusted off my old Mackie 1402-VLZ Pro mixer and began violating all the instructions in the manual.

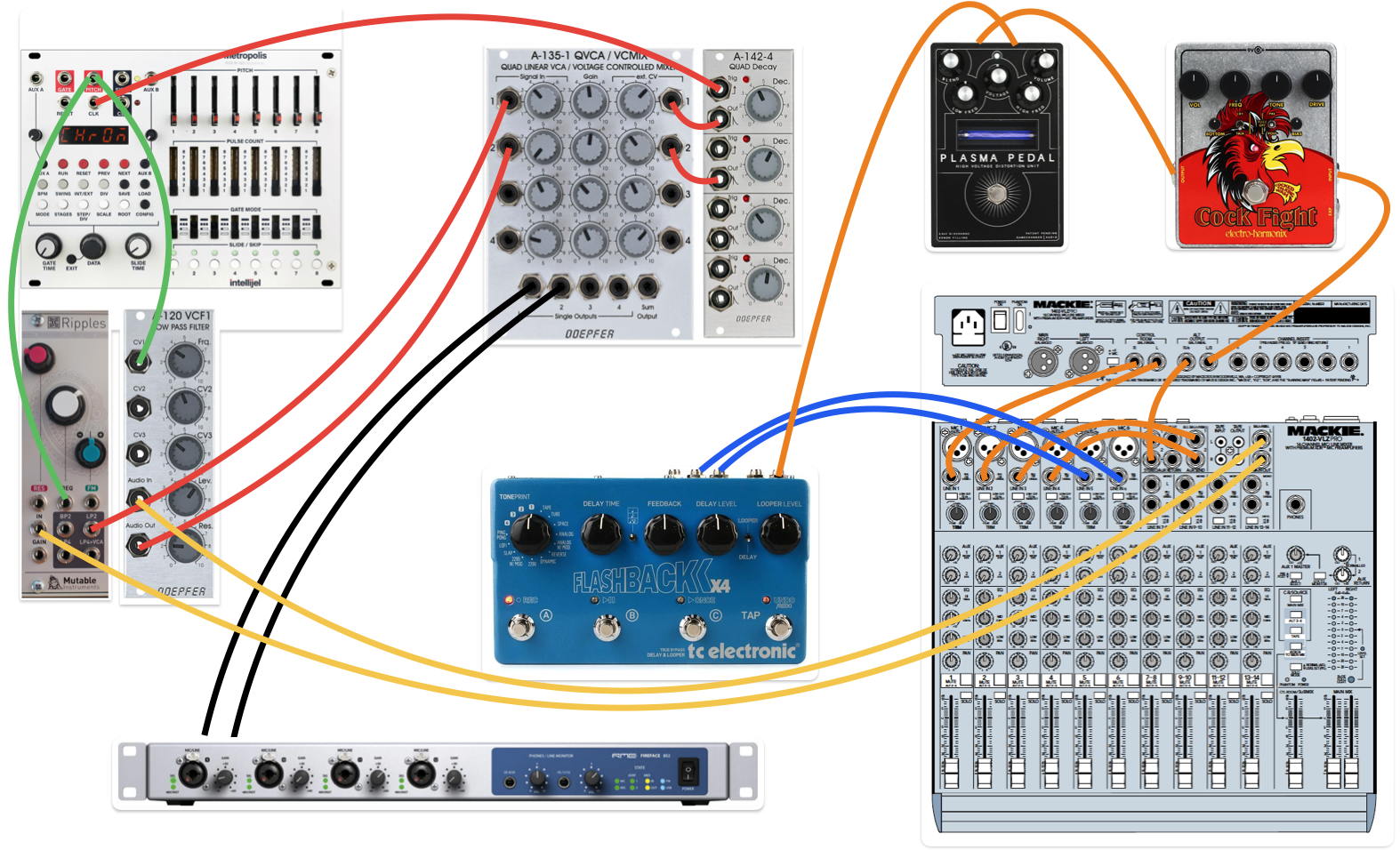

I decided right from the start to include a few pedals as part of the process because I’m no purist, and it seemed that their inclusion was common with other no-input mixing artists. As I began to experiment I felt the need for additional filtering, amplitude manipulation, and rhythmic variety. So I plugged the output of the mixer into a few Eurorack modules before recording everything into my computer. Below is a list of my patches and a diagram, but this is by no means the only approach. So give yourself the license to experiment. Pretty much any mixer will do, but it helps to have a few AUX Sends and Returns and an EQ section. Don’t worry if it’s old and noisy–the noisier the better!

Set-up using a Mackie 1402-VLZ Pro

- Control Room Output L/R >> Tracks Line Inputs 1/2

- Alt Output R >> AUX Return 2

- Alt Output L >> Cockfight Pedal Input

- AUX Sends 1/2 >> Tracks Line Inputs 3/4

- Cockfight Output >> Plasma Pedal Input

- Plasma Pedal Output >> Flashback Delay Input

- Flashback Delay Stereo Output >> Tracks Line Inputs 5/6

- Mixer Main Output L >> Doepfer VCF

- Mixer Main Output R >> Ripple VCF

- Metropolis Clock Out >> Doepfer Quad Decay

- Metropolis Pitch Out >> Doepfer VCF

- Metropolis Pitch Out >> Ripples VCF

- Doepfer VCF Out >> Doepfer VCA

- Ripple VCF Out >> Doepfer VCA

- Doepfer Quad Decay Out >> Doepfer VCA

- Doepfer VCA Out 1/2 >> RME Audio Interface >> Computer

I recorded everything as I improvised because it was apparent that the unpredictability and sensitivity of the mixer sliders and pots were such that repeatability would be challenging if not impossible. I didn’t want to neglect any sonic jewels that might emerge unexpectedly from the process.

NOTE: Be extremely cautious regarding levels, especially when using headphones. Unpredictable bursts of noise are possible from very slight adjustments.

I recorded about 90 minutes of material and then cherry-picked the best parts. As mentioned, I’m no purist, and since this was not a live performance I saw no reason to avoid post-processing and strategic editing. That said, I tried to remain true to the source and only used minimal EQ, compression, and spatialization.

Below is the resulting piece I call, Fatal Error 1402.

CONCLUSIONS/RANT

I recently saw a tee shirt for sale as merch for the New Jersey band, EROSLOVESYOU that read:

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN SOUND ART AND NOISE IS INSTITUTIONAL FUNDING

This statement rings true on many levels. Essentially, it speaks to the fact that despite all the new methods of self-dissemination that the internet and social media have created, there remain the institutional purse strings that throttle artistic innovation including major recording labels, symphony orchestras, university administrators, philanthropic foundations, broadcasting companies, etc.

This is big business at work–why take risks when your comfort zone is making so much money? Why needlessly ruffle the feathers of blue-haired patrons, philanthropists who have positioned themselves (often posthumously) to be the arbiters of culture after years of shameless exploitation, or the corpocractic puppeteers that have permeated every aspect of our lives?

Unfortunately, it is the lack of exposure and familiarity that kills an artistic movement, or at least slows it down before it forces its way into the public consciousness–like it or not. Maybe someday there will be a Grammy Award for Best Noise Album. But by then, it will be time to move on.

EXTRAS

See what’s new on our Member Resources page.

Not a Member yet? Check the Member Benefits page for details. There are FREE, paid, and educational options.

REFERENCES

“Beverley Gooch and the Evolution of Magnetic Tape.” Tennessee State Museum – Nashville Attractions, tnmuseum.org/Stories/posts/beverley-gooch-and-the-evolution-of-magnetic-tape. Accessed 17 Feb. 2024.

Boynton, Jeff. “The Black Art of Circuit Bending.” WaveInformer, 4 Feb. 2024, waveinformer.com/2024/02/04/the-black-art-of-circuit-bending/.

Cox, Christoph, and Daniel Warner. Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music. Bloomsbury Academic, An Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2015.

“Fritz Pfleumer.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 15 Jan. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fritz_Pfleumer.

Gottschalk, Jennie. Experimental Music since 1970. Bloomsbury Academic, 2021.

“History.” Buchla, buchla.com/history/. Accessed 17 Feb. 2024.

Intonarumori. (2023, November 29). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intonarumori

“Japanoise.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 1 Feb. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanoise.

Kahn, Douglas. Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts. MIT Press, 2001.

Krapp, Peter. Noise Channels: Glitch and Error in Digital Culture. University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

LaBelle, Brandon. Background Noise: Perspectives on Sound Art. Bloomsbury, 2013.

Miller, Norman. “The Theremin: The Strangest Instrument Ever Invented?” BBC News, BBC, 24 Feb. 2022, www.bbc.com/culture/article/20201111-the-theremin-the-strangest-instrument-ever-invented.

Moogmusic.Com, www.moogmusic.com/news/early-years-moog-synthesizer. Accessed 17 Feb. 2024.

Nyman, Michael. Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

“Onkyokei.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 24 May 2022, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Onkyokei.

“The Difference between Sound Art and Noise Is Institutional Funding” from Eroslovesyou.” EROSLOVESYOU, eroslovesyou.bandcamp.com/merch/the-difference-between-sound-art-and-noise-is-institutional-funding. Accessed 17 Feb. 2024.

Toshimaru Nakamura Interview, www.furious.com/perfect/toshimarunakamura.html. Accessed 17 Feb. 2024.

“Toshimaru Nakamura.” Toshimaru Nakamura, www.toshimarunakamura.com/. Accessed 17 Feb. 2024.

“Williams Mix.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 31 Jan. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Williams_Mix.