Brian Wilson, the visionary force behind The Beach Boys, has passed away at the age of 82. He leaves behind a vast and beautiful body of work that forever changed the course of popular music. Wilson’s songwriting was matched by his extraordinary vision as a producer. In this article, I’ll explore some of his finest moments as both a writer and producer, and examine how he used the recording studio as an instrument to bring his musical ideas to life.

CHILDHOOD AND MUSICAL INFLUENCES

From a very young age, Brian Wilson was immersed in music. His father, Murry Wilson, was a musician and machinist who recognized Brian’s musical abilities early on. As a baby, Brian could reportedly repeat melodies after hearing them only a few times. At age two, he was deeply moved by George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue,” an influence that would resonate throughout his career. (source)

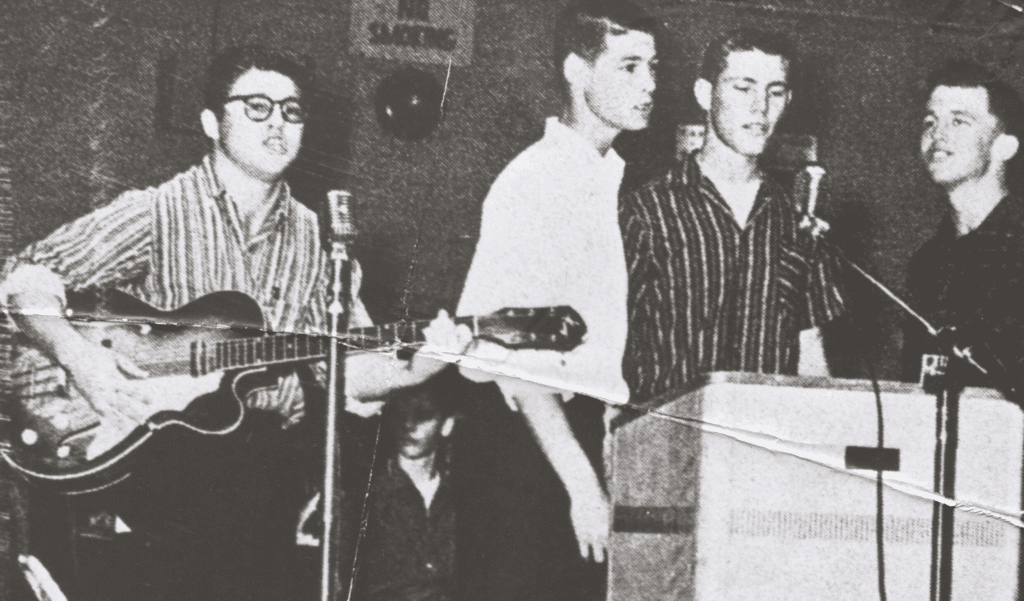

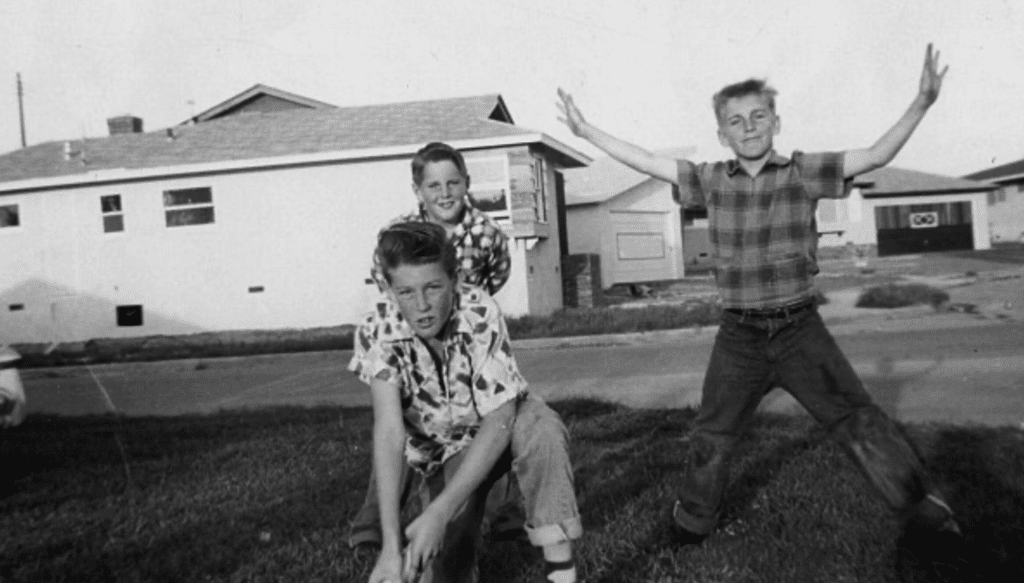

The Wilson Brothers playing in their Hawthorne, California Neighborhood

Wilson’s formative years were shaped by a love for beautiful melodies and sophisticated vocal harmonies. He was particularly inspired by singers like Rosemary Clooney and vocal groups such as the Four Freshmen, whose complex harmonies he painstakingly deconstructed and taught to his brothers, Dennis and Carl. Other key influences included the Chordettes, the Hi-Lo’s, Nat King Cole, and the boogie-woogie piano stylings he heard on the radio. Wilson’s early passion for arranging harmonies and exploring the emotional depth of music laid the foundation for his later innovations as a songwriter, composer, and producer.

I loved beautiful songs by singers like Rosemary Clooney, vocal harmonies from groups like the Four Freshmen, and the boogie-woogie. Those are the sounds that started moving around in my mind.” — Brian Wilson

Brian Wilson’s early adversity and eclectic musical influences forged a distinctive artistic vision—one that would transform American popular music and inspire generations of musicians.

A UNIQUE EAR FOR MUSIC

Wilson lived his entire musical life with significant hearing loss. Deaf in his right ear since childhood, Wilson’s impairment was the subject of speculation and family lore. The exact cause remains uncertain: Wilson himself has cited being struck in the head with a lead pipe by another child, while at other times he suggested it was the result of a blow from his father, Murry Wilson, or that he was simply born that way. Medical professionals were never able to determine a definitive cause, and some accounts point to a congenital defect known as atresia, which is the partial or complete closure of the ear canal.

Despite this setback, Wilson’s hearing loss shaped his approach to music production. He famously had Beach Boys’ albums mixed in mono, explaining that he couldn’t hear them any other way. This limitation may have contributed to his unique sense of arrangement and harmony, as he relied on his acute hearing in his left ear to craft the lush, intricate soundscapes that became his signature. (source)

FORMING THE BEACH BOYS AND EARLY SUCCESS

In 1961, at the age of 19, Wilson composed his first original melody, drawing inspiration from “When You Wish Upon a Star.” That tune would eventually become “Surfer Girl.” That same year, he joined his brothers, cousin Mike Love, and friend Al Jardine to record “Surfin’,” a track that became a local hit on Candix Records. Soon after, they became known as The Beach Boys—and would go on to redefine the sound of popular music.

After being rejected by both Dot and Liberty Records, the Beach Boys signed a seven-year deal with Capitol Records. Capitol staff producer Nick Venet, on the lookout for “teenage gold,” saw the group’s potential and advocated for the signing. On June 4, 1962, the Beach Boys made their Capitol debut with their second single, “Surfin’ Safari,” backed with “409.” The release quickly gained national attention—Billboard praised Mike Love’s lead vocal and noted the song’s strong commercial promise. “Surfin’ Safari” climbed to number 14 on the charts and received unexpected radio play in cities like New York and Phoenix, surprising even Capitol.

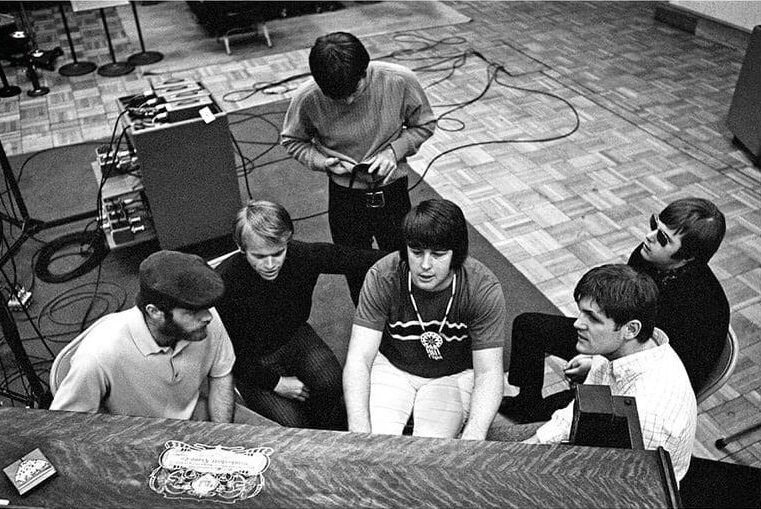

The early Beach Boys lineup performing in 1963

Many of the band’s early hit songs followed the aforementioned “teenage gold” formula, and centered around subjects like surfing, cars, and adolescent romance. Musically speaking, they were greatly influenced by Rock ‘n’ roll acts at the time, specifically, Chuck Berry. Wilson openly acknowledged that Berry’s melodies and chord patterns inspired him, especially on “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” which reworks the structure of “Sweet Little Sixteen.” Berry’s energetic lyrics and rock ‘n’ roll spirit also encouraged Wilson to write about cars and surfing, themes that became central to the Beach Boys’ early identity. As Wilson put it, “He taught me how to write rock ‘n’ roll melodies, the way the vocals should go. His lyrics were very, very good. They were unusually good lyrics. I liked ‘Johnny B. Goode,’ all about a young, little kid who played his guitar… He inspired me as a lyricist.” (source)

THE SOUND OF THE EARLY BEACH BOYS

The combination of Rock ‘n’ roll and barbershop-style harmonies resonated with the public and the band saw a series of popular songs in the early half of the 1960s. The Beach Boys followed their breakthrough with a remarkable string of hits, including 1963’s “Be True to Your School,” and a flurry of 1964 classics like “Fun, Fun, Fun,” “Don’t Worry Baby,” “I Get Around,” and “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man),” cementing their place at the heart of American pop music.

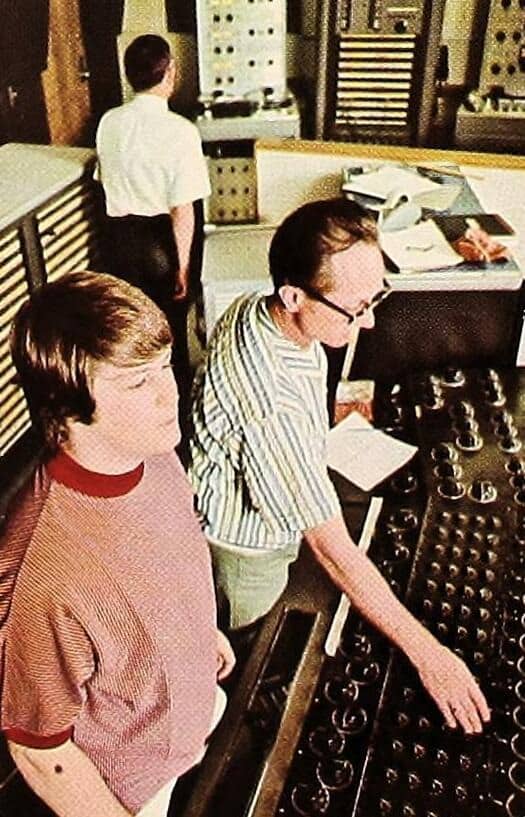

Carl Wilson, Al Jardine, Dennis Wilson, Mike Love, and Brian Wilson. The Beach Boys early lineup, which led to much of their initial success as a band

Most of the Beach Boys’ music in the 1960s was recorded by engineer Chuck Britz. He entered the recording industry in 1952, engineering big band sessions for the Armed Forces Network and the Salvation Army Band. By 1960, Britz had joined Western Recorders, where he became a central figure in the emerging Rock ‘n’ roll scene. It was there that he first crossed paths with Brian Wilson, while the Beach Boys were recording early demos. Britz quickly became a trusted collaborator, engineering and mixing most of the band’s hit records between 1963 and 1967—a period that defined Wilson’s growth as both a songwriter and producer.

The early Beach Boys sound was defined by bright, tightly arranged vocal harmonies and a clean, energetic instrumental backing that captured the spirit of California surf culture. In the studio, Brian Wilson and the band employed straightforward recording techniques typical of the early 1960s, often working with four-track tape machines. One of the hallmarks of their sound was the use of chamber reverb, especially from the echo chambers at Capitol Studios and other top Los Angeles facilities. These chambers gave their vocals and instruments a lush, spacious quality—enhancing double-tracked harmonies and creating a sense of depth that set their records apart from spring-reverb-heavy surf instrumentals of the era. (source) The band also adopted the common practice of fading out at the end of their songs, rather than concluding with a definitive ending. This technique, used on the vast majority of their tracks, contributed to a sense of momentum and ongoing energy, making their singles feel open-ended and radio-friendly. Together, these production choices—simple but effective recording setups, natural chamber reverb, and the signature fade-out—helped establish the Beach Boys’ early sound as both instantly recognizable and enduringly influential.

Wilson at the board with engineer Chuck Britz, who recorded much of the Beach Boys’ most popular works.

WHAT SET WILSON APART

Even in these early songs, Wilson presented a unique degree of introspection, sadness, and expression of vulnerable masculinity that was not common in much popular music at the time. “In My Room” (1963), co-written with Gary Usher displays a certain sensitivity that Wilson became known for. “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” (1964) reflects the Beach Boys’ evolving view of growing up by expressing the anxieties and uncertainties that come with the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Unlike the band’s earlier songs focused on carefree teenage themes, “When I Grow Up” delves into more reflective and emotional territory. The narrator questions what life will be like when he grows up, wondering if he will still enjoy the same things, whether he will settle down or travel the world, and if he will love his wife for the rest of his life. The song captures a sense of apprehension about the future and the responsibilities of adulthood. (source)

EVOLVING PRODUCTION TECHNIQUES

Wilson was the Beach Boys’ undisputed leader in the studio from the very beginning. By the mid-1960s, he had taken over as the group’s producer, making the Beach Boys one of the rare bands of the era to work without an outside producer. Wilson’s perfectionism, innovative use of double-tracked vocals, and incorporation of classical, jazz, and unconventional recording techniques set the group apart. His vision and command in the studio were instrumental in shaping the Beach Boys’ sound and driving their early success. In the mid-1960s, as their British counterparts The Beatles released music that incorporated experimental recording techniques (in part thanks to the brilliant Abbey Road Studios recording staff), The Beach Boys charted a similarly avant-garde path. I’d argue that “California Girls” (1965) marked a significant turning point for the band’s sound:

- “California Girls” features a lush, orchestral prelude that sets it apart from the band’s earlier, more straightforward surf rock tracks. Brian Wilson conducted the session like an orchestra, incorporating a sophisticated, cinematic introduction that his father, Murry, initially felt was too complex for a pop song (source)

-

The song was recorded using Columbia Studios’ state-of-the-art 8-track recorder. This allowed for double-tracked lead vocals and the spreading of the Beach Boys’ harmonies across multiple tracks, resulting in a richer, more layered vocal sound than their previous work. (source)

-

Wilson’s meticulous approach led to 44 takes of the backing track before he was satisfied, demonstrating a new level of studio perfectionism.

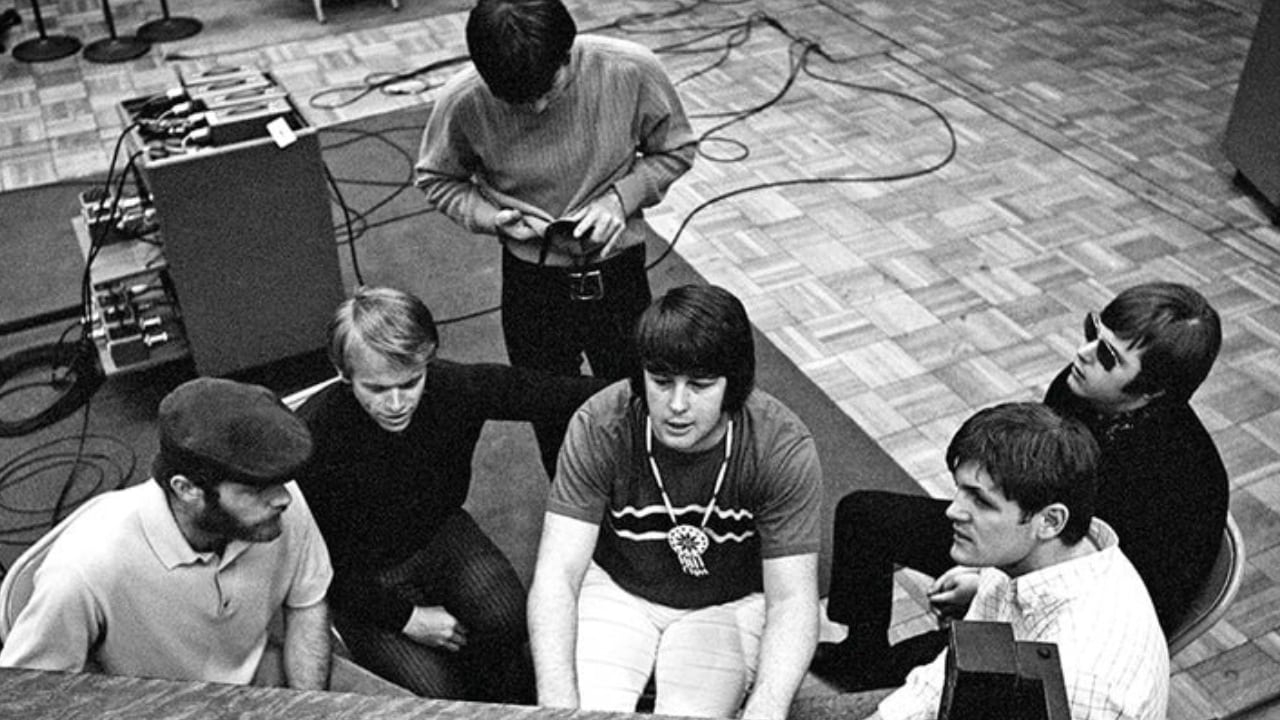

The Beach Boys hard at work at Columbia Studios

PET SOUNDS

Wilson’s next work, Pet Sounds, continued to move the Beach Boys away from the Rock ‘n’ roll-inspired surf and car songs of their early albums. Instead, the melancholic lyrics written with Tony Asher, Wilson’s ambitious production, use of outside musicians, and innovative studio techniques resulted in a sophisticated, emotionally resonant album that could not be replicated live and set a new standard for pop music artistry. (source)

The Wrecking Crew, a group of session musicians that Wilson brought on during the recording of Pet Sounds

These innovations solidified Pet Sounds as a landmark in music production and a turning point in the Beach Boys’ artistic evolution. Here are a few innovative techniques employed on Pet Sounds:

1. Orchestral Instrumentation and Dense Harmonies on “Wouldn’t It Be Nice”

Right from the album’s opening track, “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” it’s immediately clear that the level of production had reached new heights compared to the band’s earlier work. On Pet Sounds, Wilson employed The Wrecking Crew, a renowned team of session musicians often hired by influential producer Phil Spector—who would later become notorious for his criminal conviction. Wilson produced the track between January and April 1966, working with both the Beach Boys and the 16 studio musicians who contributed an eclectic array of instruments, including drums, timpani, glockenspiel, trumpet, saxophones, accordions, guitars, pianos, and upright bass. The harp-like sound heard in the intro comes from a 12-string mando-guitar, recorded by plugging it directly into the console. Unusually for a pop song, one section features a ritardando—a gradual slowing down of tempo. The band had difficulty meeting Wilson’s high standards for the complex vocal arrangements, making this the most time-consuming recording session of the entire album. Have a listen to the breathtaking isolated vocals of “Wouldn’t It Be Nice”:

2. Plucking Piano With A Bobby Pin and a Bicycle Horn on “You Still Believe In Me”

The 2nd song on Pet Sounds continued with experimental production techniques. On January 24, 1966, the introduction to what would become “You Still Believe in Me” was recorded at Western Studios. For the backing track of this section, Wilson and Asher created an ethereal effect by plucking the strings of a piano with a bobby pin. Asher explains:

“We were trying to do something that would sound sort of, I guess, like a harpsichord but a little more ethereal than that. I am plucking the strings by leaning inside the piano and Brian is holding down the notes on the keyboard so they will ring when I pluck them. I plucked the strings with paper clips, hairpins, bobby pins and several other things until Brian got the sound he wanted.” (source)

3. Literally Every Aspect of “God Only Knows”

From the then-bold decision to use the word “God” in a pop song, to the complex harmonic tension woven throughout, to the echo-drenched percussion and the unparalleled counterpoint harmonies at the song’s climax, God Only Knows might just be the greatest pop song ever written—if there were a way to measure such a thing (there isn’t). Wilson had previously recorded strings as overdubs atop Beach Boys’ backing tracks, but recorded them alongside the traditional rock instrumentation on God Only Knows, resulting in a truly ethereal foundation upon which the song’s haunting melody would be sung upon.

4. Altering Tape Speed and Sound Effects in “Caroline, No”

The melancholic album closer features a handful of interesting production techniques. During the final master, the playback speed of the tape was altered (by 6%) so that the song registered one semitone higher, which made the lead vocal sound more childlike. Wilson wanted a non-musical tag to close the song and album, ultimately combining recordings of his dogs Banana and Louie (which inspired the album’s title), with a recording of a train taken from a 1963 effects album Mister D’s Machine (“Train #58, the Owl at Edison, California”).

Pet Sounds is brilliant, from front to back. Not only in the quality of songs, arrangements, and performances, but the creative techniques employed during its recording. After the release of the album in May 1966, the Beach Boys found themselves at a creative crossroads. While the album is now hailed as a masterpiece and has consistently ranked among the greatest albums of all time, its initial commercial performance in the United States was only moderate, peaking at number 10 on the Billboard chart and selling about 500,000 copies—fewer than their previous records.

Members of The Beach Boys recording Pet Sounds. Many images show most of the group around a pair of microphones, with Mike Love in front of his own.

GOOD VIBRATIONS

Despite the lukewarm commercial response, Brian Wilson was undeterred. He was already envisioning his next project—one that would push the boundaries of pop music even further. The seeds of “Good Vibrations” had actually been planted during the Pet Sounds sessions. Inspired by a childhood lesson from his mother about dogs sensing people’s “vibrations,” Wilson became fascinated with the idea of capturing positive energy and emotion in music. He began developing “Good Vibrations” as a musical experiment, initially intending it for Pet Sounds, but ultimately setting it aside as the album neared completion. (source)

The creation of “Good Vibrations” marked a radical departure from both the band’s earlier surf hits and even the ambitious methods of Pet Sounds. The song featured an astounding 14 key changes, and to go along with the song’s ever-changing tonality, Wilson pioneered a “modular” recording approach: instead of recording the song in a single session, he broke it into dozens of musical fragments or “feels,” each representing a different mood or emotion. These modules were recorded over months, across four different Hollywood studios, and with more than 30 session musicians. Wilson then meticulously pieced these fragments together, essentially inventing a “cut and paste” technique that predated digital editing by decades. (source)

The sessions for “Good Vibrations” were famously complex and costly, consuming over 90 hours of tape and tens of thousands of dollars—the most expensive single ever produced at that time. (source) Wilson experimented with a wide array of sounds and instruments, including the Electro-Theremin (an electronic instrument that gave the song its signature eerie wail), jaw harp, cello, and layered harmonies. He also used advanced studio techniques like extensive tape splicing, overdubbing, and recording in different studios to achieve unique sonic textures. (source)

Often mistaken for a theremin, the instrument on ‘Good Vibrations’ was actually its cousin: the electro-theremin

The result was a self described “pocket symphony” that defied conventional song structure, shifting abruptly between sections and moods yet holding together as a cohesive, exhilarating whole. Released in October 1966, “Good Vibrations” topped charts worldwide and was immediately recognized as a groundbreaking achievement, cementing Brian Wilson’s reputation as one of pop’s most innovative producers and composers.

SMILE, SURF’S UP, AND BEYOND

Wilson’s follow-up to “Good Vibrations” maintained his lofty ambitions for the direction of popular music. He began work on SMiLE, described as a “teenage symphony to God,” applying the modular recording techniques and experimental spirit of “Good Vibrations” to an entire album. He collaborated closely with lyricist Van Dyke Parks, aiming for even greater artistic heights. The sessions, however, became increasingly fraught. One such session stands out: “Fire” (also known as “The Elements – Part 1” and “Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow”) was inspired by Catherine O’Leary and the Great Chicago Fire. The piece was intended as part of “The Elements,” a four-part suite representing the classical elements: Air, Fire, Earth, and Water. Wilson recorded “Fire” on November 28, 1966, at Gold Star Studios with 15 session musicians, including three bassists, four flutists, and a string sextet. To heighten the atmosphere, he asked everyone in the studio to wear fire helmets and placed a bucket of burning wood nearby to fill the room with the scent of smoke. The intense session was designed to evoke the chaos of a blaze, but within days, a nearby building burned down, and Wilson became convinced that the music had caused it. Disturbed by the coincidence, he shelved the track, which many of his friends and collaborators later cited as a turning point in his psychological decline and the unraveling of the SMiLE project.

Wilson’s perfectionism, escalating drug use, and mounting pressure to outdo “Good Vibrations” led to delays, creative disagreements within the band, and ultimately, a sense of unraveling. Capitol Records had already begun advertising SMiLE with the promise of “other new and fantastic Beach Boys songs,” but the project stalled as Wilson struggled with indecision and self-doubt, fearing he could never surpass his previous work.

By mid-1967, SMiLE was shelved, and the band hastily assembled the album Smiley Smile, which included “Good Vibrations” at Capitol’s insistence—against Wilson’s wishes. In the aftermath, Brian Wilson’s mental health deteriorated. He gradually withdrew from leadership, and the Beach Boys’ commercial momentum faltered in the U.S. as the late 1960s music scene shifted. Although the Beach Boys continued to record and perform, their creative direction was no longer driven by Brian’s singular vision.

Wilson, during the infamous “fire” session at Gold Star Studios in 1966

That said, one of his finest works, “Surf’s Up”—a song from the discarded SMiLE—appeared on The Beach Boys’ 1971 album of the same name. The song’s eclectic arrangement, sorrowful melody, and extended choral outro showcased Wilson’s compositional brilliance and emotional depth, standing as a haunting epitaph to the band’s most ambitious era. After the creative heights of the 1960s, Brian Wilson’s life was marked by decades of struggle with mental health, addiction, and periods of withdrawal from music and public life. Diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, Wilson endured persistent hallucinations, depression, and paranoia, which were compounded by substance abuse and personal turmoil. His family’s intervention led to years under the controversial care of psychologist Dr. Eugene Landy, whose methods were both credited with helping Wilson regain some stability and criticized for their controlling nature.

BRIAN WILSON’S RETURN, THE TRIUMPH OF SMILE, AND HIS FINAL YEARS

Following several incredibly challenging decades marked by personal struggles, seclusion, and a decline in musical output, Brian Wilson gradually began to reemerge. Ultimately, Wilson’s resilience—and the support of his second wife, Melinda, whom he married in 1995—helped him reclaim his health and creativity, allowing him to return to music and the stage in the late 1990s and beyond.

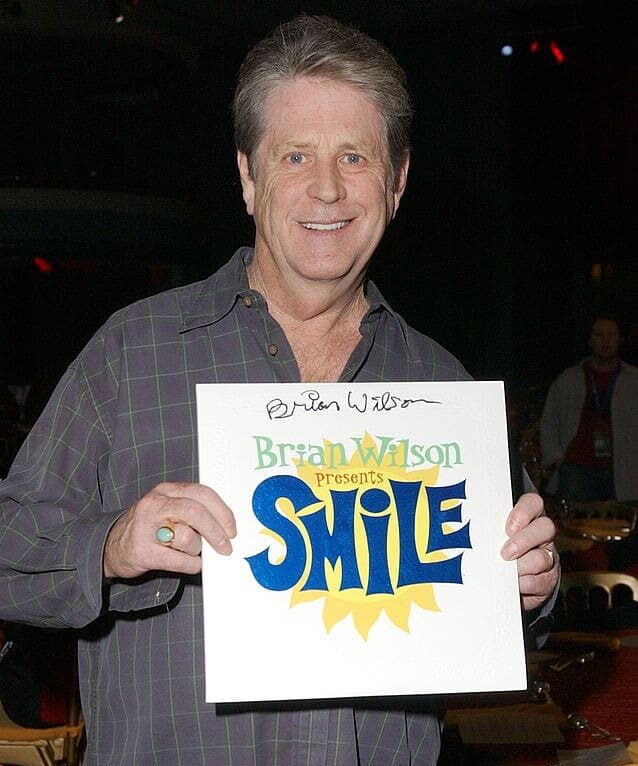

One of the most remarkable chapters in Wilson’s later career was his decision to revisit SMiLE, the legendary unfinished album he had abandoned in 1967. The project had long haunted him, symbolizing both his artistic ambition and the pressures that contributed to his breakdown. In the early 2000s, encouraged by his bandmates and collaborators, Wilson began rehearsing SMiLE for live performance. The process was emotionally fraught, triggering old anxieties and even panic attacks, but also proved therapeutic. In 2004, Wilson and his band premiered SMiLE in London to rapturous acclaim, then recorded a studio version—Brian Wilson Presents SMiLE—which was released that September.

The album was a triumph, earning universal critical praise, a Grammy Award, and strong chart success. For Wilson, completing SMiLE was not just a creative milestone but a personal victory over the traumas of his past. He later described holding the finished CD to his chest, visibly moved by the sense of closure and accomplishment. (source)

Wilson, holding a copy of 2004’s SMiLE

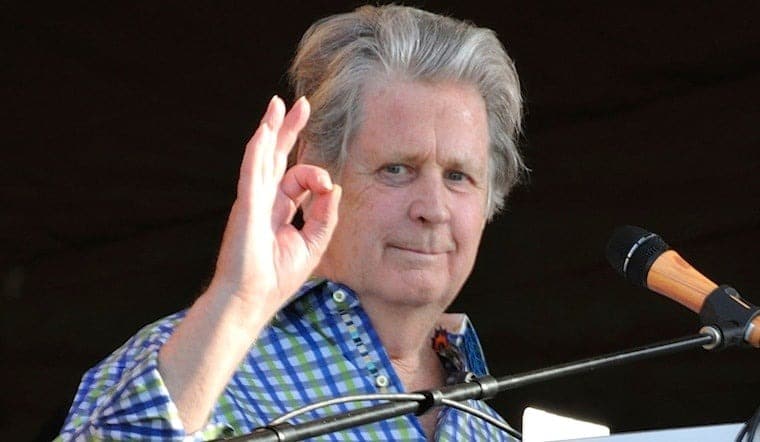

Wilson’s return to the stage was equally significant. After decades away from touring, he assembled a large, multi-instrumentalist band capable of faithfully recreating the intricate arrangements and harmonies of his studio masterpieces. From 1999 onward, Wilson toured extensively, performing not only Beach Boys classics but also ambitious full-album concerts of Pet Sounds and SMiLE, delighting audiences worldwide. His bandmates and fans alike noted the authenticity and richness of these performances.

Despite ongoing health challenges, Wilson remained committed to music and performance well into his later years. He continued to tour, record, and inspire, always mindful of the need to prioritize his mental health. His final concert took place on July 26, 2022, at Pine Knob Music Theatre near Detroit, where he was joined by longtime collaborators and fans who celebrated his enduring legacy.

Wilson toured well into his later years, sharing his vast catalog of brilliant musical works with new generations

Brian Wilson passed away at the age of 82 on June 11th, 2025. The songs he left us are absolute gifts, and the creative methods he used to capture his compositions have and will continue to influence music producers of all genres. I personally can’t put into words how inspirational and meaningful his music has been to me, and simply feel a sense of deep gratitude that I lived at the same time as one of the greatest musical geniuses ever.