Zimoun is a Swiss artist who creates monumental sound art installations that often involve the use of hundreds of DC motors to drive very simple sound-making mechanisms. Many of his works rely on the creation of sound via physical devices where friction and percussive actions produce sonic textures designed specifically for the space. The work is both visually and sonically stunning and having been a fan for several years, I decided to reach out to the artist with some questions regarding his background and artistic practice (see below).

Zimoun portrait by Peter Hauser

SOUND INSTALLATION ART

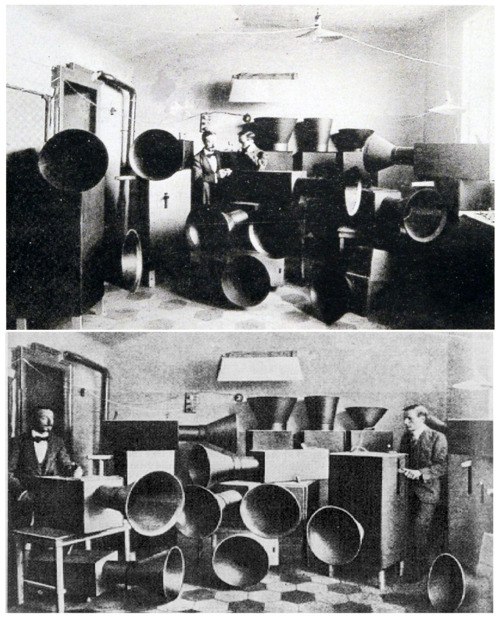

Sound installations can be found in museums, galleries, and public spaces. The genre can be traced back to the work of Italian futurist, Luigi Russolo in the early 20th Century, who explored the use of custom-built instruments (Intonarumori) to embrace the use of noise as an alternative to traditional methods of music and sound-making. Pivotal pieces were later produced by Marcel Duchamp, Bill Fontana, John Cage, Robert Morris, Alvin Lucier, Max Neuhaus, and others.

Luigi Russolo’s Intonarumori (Intonarumori)

Sound installations typically involve electronics, computer-generated sound, and the use of speakers and/or microphones to transduce electrical energy and sound waves. Interactive components are also quite common as many artists employ various types of sensors that allow the audience to influence the sonic outcome. Immersive installations surround the viewer/listener with sonic and visual content creating environments that can range from overwhelming to meditative.

250 prepared ac-motors, 325kg roof laths, 1.8km rope – Zimoun 2015

Installation view: Knockdown Center NYC

What attracts me to the work of Zimoun and the impetus for this article/interview is his focus on acoustic/mechanical devices as the primary means of sound production. This approach lies in stark contrast to omnipresent tech-driven methods that sometimes result in gimmickry or gratuitous interaction-based work. Following the interview below is a video compilation that demonstrates the astounding breadth and magnitude of Zimoun’s work.

INTERVIEW WITH ZIMOUN

PHILIP MANTIONE: Can you talk a bit about your background and how you came to work with sound?

ZIMOUN: Since my childhood, I have played music and learned various musical instruments. At the same time, I have always engaged in visual activities, experimenting with paint, photography, drawing, or old Xerox printers, etc. Thus, for as long as I can remember, I have been involved in both musical and visual activities. Simultaneously, I became interested in minimalism, reductive methods, and principles at the age of a teenager. One day while working on multichannel compositions later on, I recorded various sounds and noises of paper with microphones, electronically processed these sounds and built a composition out of them, and then played the resulting piece through numerous speakers distributed in the room. An exploration of sound as space and multiple sound sources within the space.

“…to set materials in motion inside the actual space and thus produce 3-dimensional sound fields.”

In this process and based on my ongoing interest in minimalist approaches and the associated attempt to reduce my work to only the most essential elements, I asked myself how I could create these sounds in real-time within the space without first recording, processing, spatially orchestrating, and then playing them through speakers. I wished to generate the spatially distributed sounds in real-time in a very immediate way. This moment marked the beginning of my work with physical material and mechanical systems, to set materials in motion inside the actual space and thus produce 3 dimensional sound fields.

PM: You use recycled materials to create hundreds of structurally identical devices to generate sound and rich chaotic textures. For me, the work evokes concepts relating to mass production, conformity versus individuality, order within chaos, and the resonant nature of materials and spaces. Can you talk about the underlying conceptual framework that informs the work?

Z: Your listed points interest me. My work involves exploring opposites that can exist within the same entity, even though they may seem contradictory: simplicity and complexity, organic and artificial, mass and individuality, order and chaos, precision and imperfection, technology and primitiveness… In the end, all these opposites lead to questions about perception. Why do we perceive something as complex, even when we can see that simplicity underlies the system? How does our perception work, and how do we create an assumed reality? Among other things, I try to investigate complexity using the simplest possible systems and principles.

PM: Many of the pieces create sound by activating resonant bodies such as cardboard or through friction and the vibration of objects. When developing a work, do you consider the possible spectral range of frequencies to be produced? Are you looking for a variable range or one consistent fundamental frequency?

Z: I’m less interested in the mathematical or physical analysis of specific frequencies and more focused on their perception and subjective impact. I aim to create fields and situations that invite both myself and visitors to make observations, establish individual connections to various themes, and inspire potential explorations.

PM: Most of the work seems to be site-specific. How do the acoustics of the room figure into your concept in the early stages of development? Do you take any sonic or physical measurements of the space as part of the process? Does the geographical location or architectural relevance of the space come into play?

43 prepared dc-motors, 31.5kg packing paper – Zimoun 2013

Installation view: Orbital Garden Bern, Switzerland

510 prepared dc-motors, 2142m rope, wooden sticks 20cm, 2019

Installation View: NYUAD Art Gallery, Abu Dhabi

Z: Yes, my installations are mostly site-specific, designed for the space in which they are presented. Therefore, the exhibition space, its architecture, materialization, and the spatial characteristics play a central role in the conceptual development, proportions, and development of a work. The space itself is usually the starting point. Then numerous other factors come into play during project development, such as the duration of the exhibition, the time available to set up a work, the number of people helping with the setup, and the budget within which the work can be realized. It is a matter of assembling numerous puzzle pieces in the most promising way possible.

At the same time, I am always experimenting with new ideas and methods here in my studio, building prototypes, observing them, further developing, and refining them. Some of these are created independently of a specific space, while others are already developed with the specific space in mind. This process of testing and experimentation often goes through numerous prototypes and trials until the final system to be used crystallizes. It is often a similar process and yet practically never exactly the same. I find the way to engage with the space particularly inspiring each time. There are spaces where I tend to work with a larger physical volume within the room, in a sculptural and bodily manner, while other spaces are inspiring for a ceiling-hung work or a large-scale floor installation.

Zo

Zimoun studio

“…the space can act as an amplifier, filter, or an effect, and it usually behaves differently in different positions within the space.”

The acoustic properties of the space itself always play a relevant role in the overall sound. The space allows the work to be experienced from various perspectives. In that sense, the space can act as an amplifier, filter, or an effect, and it usually behaves differently in different positions within the space. This makes the space an interesting tool to explore the sounds in diverse ways – next to be the host of the work.

“…it’s not about reproductions, but productions.”

What I don’t do, however, is measure the space acoustically. It’s not about representing a specific sound. In this sense, the approach is entirely different from, for example, a chamber orchestra performing a particular piece. In that case, it’s about reproduction—aiming to achieve a very specific sound as precisely as possible. In my case, however, it’s not about reproductions, but productions. The space itself contributes its acoustic properties and unique sound characteristics to the final work, just like the material does. The space is part of the orchestra – or of the instrument.

PM: The use of hundreds of DC motors to drive some sort of repetitive motion is a consistent element in your work. What are the challenges in terms of driving so many devices? Is a particular sort of power distribution device or circuitry required?

Z: I aim to keep my works as simple and primitive as possible while simultaneously creating complexity. Technically, the pieces are usually very straightforward: motors interacting with materials through a steady power supply. It’s essentially a power supply delivering a specific voltage to a motor. The complexity then arises from the interaction between rotation and material properties.

658 prepared dc-motors, cotton balls, cardboard boxes 70×70×70cm – Zimoun 2017

Installation view: Le Centquatre-Paris, France

PM: The pieces are both visually and sonically satisfying. When developing a new piece, do visual or sonic ideas take precedence, or do they emerge together?

Z: Yes, everything merges together; no element is more important than another, and they somehow all influence each other to some degree.

PM: You seem to focus on acoustic sound generation driven by mechanical sculptures. Have you considered or experimented with the use of electronic sound in your installations?

Z: At the very beginning, I also created purely acoustic installations, distributing sounds through speakers in the space. But as I mentioned earlier, I then became interested in more direct ways of sound production, without files, recordings, speakers, or amplifiers. Since I am interested in the pure and maximally-reduced, I have no desire to mix these elements. On the other hand, I work differently in my pure audio works, and there I do still also experiment with multi-channel sound systems and various musical instruments.

PM: You’ve referred to your installations as compositions, but you also have recorded music as well. Can you describe any differences or similarities in the way you write music compared to your installation work? Is there any overlap between the two in terms of content?

Z: In both my installations and music, I try to create explorable spaces—like states or organisms that, within a defined framework, go out of control and thus develop an apparent liveliness or complexity. They are usually not compositions that progress from A to B or Z, whether in music, installations, or sculptures. This approach is characterized by a minimalist and reduced methodology.

PM: Can you talk about the technology (software and/or hardware) you use for your recorded music?

Z: I like to start from a reduced baseline to explore possibilities and limits and to engage with materials, conditions, and potentials. Technological possibilities can be one element, but I don’t see myself at the forefront of technology or fully exploring it. Instead, technology serves as a tool that can flow into my creations.

PM: Are there any musical or installation artists that have particularly influenced you?

Z: I see almost everything as a source of inspiration. This can even include artistic works that don’t interest me because they confront me with what I’m not interested in. Inspiring things can come from various fields and are by no means limited to art or music. I’m interested in people who delve deeply into specific subjects, whether it’s art, cooking, physics, philosophy, or really anything else. It’s the world around me that interests, fascinates, and inspires me—from nature itself to societal issues, art, architecture, and many other fields. But to mention at least one artist, as a teenager, I engaged more deeply with John Cage and his views on sound, noise, and silence.

VIDEO COMPILATION

ARTIST BIO

Zimoun lives and works in Bern, Switzerland. His work has been presented internationally, recent displays of his work include exhibitions at the Museum Haus Konstruktiv Zurich; Museum of Contemporary Art MAC Santiago de Chile; Nam June Paik Art Museum Seoul; Kuandu Museum Taipei; Art Museum Reina Sofia Madrid; Ringling Museum of Art Florida; Mumbai City Museum; National Art Museum Beijing; LAC Museum Lugano; Seoul Museum of Art; Museum MIS São Paulo; Muxin Art Museum Wuzhen; Kunsthalle Bern; Taipei Fine Arts Museum; Le Centquatre-Paris; Museum of Contemporary Art Busan; Museum of Fine Arts MBAL; Tinguely Museum Basel; Kunstmuseum Bern; Blackburn Museum; Museum Collection Lambert Avignon; Contemporary Art Museum of Estonia EKKM, among others.

Zimoun is best known for his installative, generally site-specific immersive works, mostly based on recycled materials. He employs mechanical principles of rotation and oscillation to put materials into motion and thus produce sounds. For this, he principally uses simple materials from everyday life and industrial usage, such as cardboard, DC motors, cables, welding wire, wooden spars, or ventilators. For his works, Zimoun develops small apparatuses which, despite their fundamental simplicity, generate a tonal and visual complexity once activated – particularly when a large number of such mechanical contraptions, generally hundreds of them, are united and orchestrated in installations and sculptures. (Text by Ulf Kallscheidt. Translation by Aoife Rosenmeyer. Sikart Lexicon.)

Read more here.

RELATED BOOKS

If you are interested in sound art and installations, check out the following books:

- Cage, John, and Richard Kostelanetz. John Cage: An Anthology. Da Capo Press, 1991.

- Cox, Christoph, and Daniel Warner. Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music. Bloomsbury Academic, 2019.

- Kahn, Douglas. Noise, Water, Meat: History of Voice, Sound, and Aurality in the Arts. MIT Press, 2015.

- Kim-Cohen, Seth. In the Blink of an Ear: toward a Non-Cochlear Sonic Art Seth Kim-Cohen. Bloomsbury Academic, 2023.

- LaBelle, Brandon. Background Noise: Perspectives on Sound Art. Bloomsbury Academic, an Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc, 2020.

EXTRAS

Want to win a free license to Kontakt 8? Be one of the first 1000 people to FOLLOW WAVEINFORMER ON INSTAGRAM to be automatically entered to win one of three full-version Kontakt 7 licenses! Read more.

Assess your knowledge of essential audio concepts using our growing catalog of online Quizzes.

Explore more content available to Subscribers, Academic, and Pro Members on the Member Resources page.

Not a Member yet? Check the Member Benefits page for details. There are FREE, paid, and educational options.