Silence in music has been used for dramatic effect, textural contrast, and propelling narratives by many composers in practically all genres. In this article, I will explore some perspectives on the use of silence and provide some examples.

GET OUT OF WHATEVER CAGE YOU’RE IN

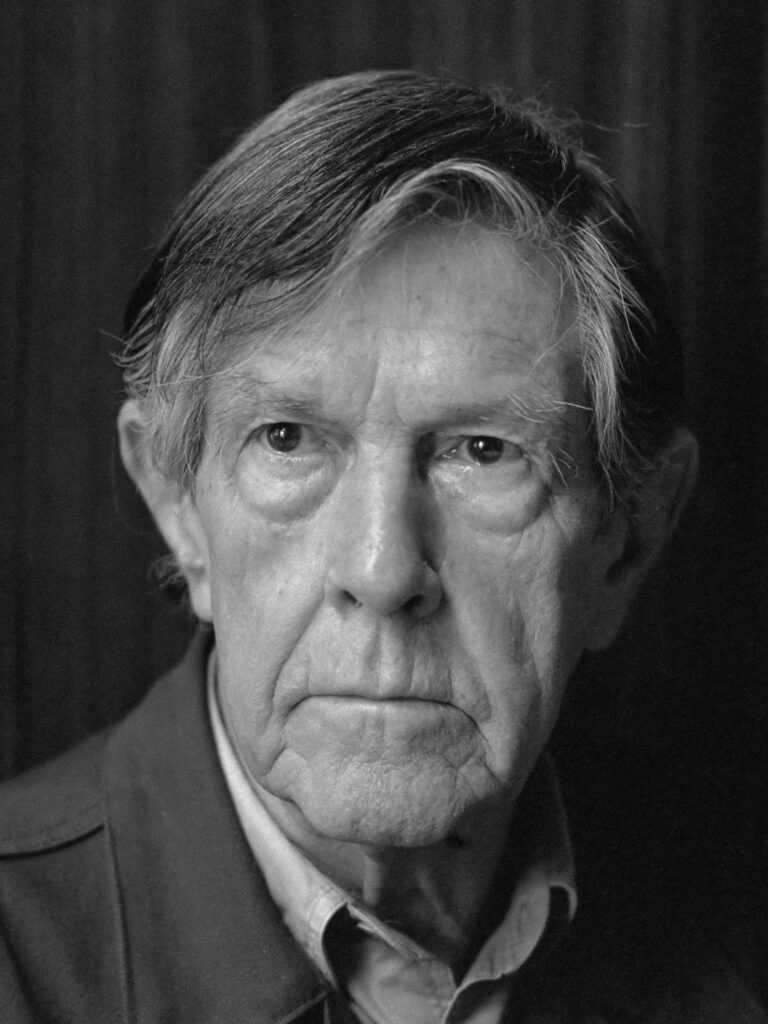

This was the advice given to young composers by John Cage, one of the most influential composers of the 20th Century. Cage for a controversial figure in art and music and many of his ideas were scoffed at by his peers. Perhaps his most contentious piece was 4’33”. This was a solo piano work originally performed by David Tudor in Maverick Concert Hall, Woodstock, NY in 1952. The piece unfolds in 3 movements but at no time does the performer ever play a note. The movements are marked by opening and closing the piano keys cover. It created quite an uproar at the time and people still talk about it over 70 years later. This is striking for a piece where no “music” is actually played.

John Cage (Bogaerts, Rob / Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Many have misconstrued Cage’s idea with this piece as a statement that silence is music. I think what he was really saying was that there is no such thing as silence in terms of the absence of sound. And that all sounds could be considered music. During the piece, ambient sounds from outside of the concert space were heard as well as the rustling of impatient and grumbling audience members. His intention was to open our ears to the world of sound around us while simultaneously undermining the traditional roles and expectations of concertgoers and performers. See a performance of 4’33” by pianist, Ji Liu here.

Cage used silence as a structural element in other works as well. If you’re interested in reading more about John Cage I suggest these two sources:

Silence: Lectures and Writings by John Cage

John Cage: An Anthology edited by Richard Kostelanetz

SILENCE IN FILM–NOT SILENT FILM

One of the greatest director/composer collaborations involved Bernard Herrmann and Alfred Hitchcock. Herrmann wrote the scores for classics like The Trouble with Harry, Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho, and others. It’s been said that Hitchcock did not want any music during the famous shower scene in Psycho but later changed his mind after hearing Herrmann’s iconic screeching strings gesture that accompanied the stabbing. He is also quoted as saying. “Silence is often very effective and its effect is heightened by the proper handling of the music before and after.” (source)

Before the knife attack in Psycho, we can hear only the ambience of the bathroom–toilet flushing, a squeaking water spigot, soap being unwrapped, water running, etc. There is no “music” until the stabbing begins about a minute into the scene. Had there been some sort of underscore before that, the feeling of suspense would not have been as great. Hitchcock expressed that music and sound, or the strategic absence of it were important factors in driving the narrative stating, “…careful use of sound can help strengthen the intensity of a situation”.

CLASSICAL MUSIC EXAMPLES

In the Finale of Jean Sibelius’ Symphony No. 5 there are extraordinary pauses between tutti orchestral hits on the V chord that dramatically increase the anticipation of the final resolution (see 9:39 in the video).

In Samuel Barber’s masterpiece, Adagio for Strings the movement is so slow and flowing that silence between the phrases happens naturally and is almost like the space between breaths. I find it to be one of the most beautiful pieces ever written for strings. Listen to the pause around 5:50.

SILENCE IN MUSIC – MULTIPLE GENRES

In Roxy Music’s In Every Dream a Heartache there’s a 10-second pause that starts around 4:11. “On the original vinyl LP, the song was the last one on side A, and appeared to fade out into the run-out groove, only to return, heavily processed with phase shifting techniques. This audio pun is preserved on the CD release” (source). Listen to it here.

In King Crimson’s 21st Century Schizoid Man there is a break sequence with dead silence between the phrases starting around 4:40. Very effective, unpredictable, and neurotic. It works well to anticipate the groove that settles in directly afterward.

The Doobie Brothers’ Long Train Running has a brief but effective pause right before the return of the classic opening riff around 2:40.

In Radiohead’s Just there is a silent break at around 2:35.

Led Zeppelin’s Good Times Bad Times has a classic pre-solo break around 1:29.

System of a Down’s Chop Suey has an intense section around :46 with alternating silence and aggressive phrases that seem random at first but lock into the groove when the drums come in.

Metallica’s Sad But True has an extended pause right after a short intro around :17.

Aerosmith’s Living on the Edge has an extended pause around 3:33 that creates a feeling of suspension.

In AC/DC’s ’74 Jailbreak, there is dead silence at 3:25 right after the line “He made it out”. The silence precedes the line, “With a bullet in his back”.

In Arctic Monkeys’ Perhaps Vampires is a Bit Strong But… there is a long pause around 3:28 until a distant yelling shouts out, “All you people are vampires”.

In Animal Collective’s Native Belle, there are many silent pauses after a very long fade in at the beginning.

The opening of Tessela’s Nancy’s Pantry sets the tone for the noisy and distorted grooves to come. The silence sort of frames the crunchy percussive hits.

Perhaps the mother of all uses of silence was by Vulfpeck who created an entire album of silence called, Sleepify. The playlist looks like this:

- Z

- Zz

- Zzz

- Zzzz

- Zzzzz

- Zzzzzz

- Zzzzzzz

- Zzzzzzzz

- Zzzzzzzzz

- Zzzzzzzzzz

Each track is about :31 of silence. The intention of the band was to finance their upcoming tour so they exploited Spotify’s royalty system by asking their fans to stream the album as they slept. Spotify considers anything over :30 to be a legit play. Supposedly, the band earned about $20k in royalties. (source)

It warms my heart to think of Spotify getting played for once. Of course, they removed the album shortly thereafter.

CONCLUSIONS

Sound is a powerful medium but sometimes, as in the visual arts, it is the negative space that provides the perfect context and defines a great work. Silence can drive a narrative, accentuate emotional impact, supply contrast to an otherwise one-dimensional texture, or surprise the listener in effective and engaging ways. It can provide an opportunity for what composer Pauline Oliveros referred to as deep listening to the sounds in our environment. It can be used as a structural component or motivic device. In the case of Vulfpeck, it can even be used to exploit the exploiters. With all that has been written about making sound–generating it, molding it, processing it, recording it, mixing it, mastering it–it seems a little silent treatment is worth considering. After all, there is “silence” before and after every piece of music, so why stop there?

EXTRAS

See what’s new on our Member Resources page.

Not a Member yet? Check the Member Benefits page for details. There are FREE, paid, and educational options.